Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir form one of the most common forest associations in the Rocky Mountains and parts of the Cascades. In California, this is one of our rarest subalpine forest vegetation alliances. These two species occur in only a few places in the state–often not even together unlike in the rest of their range. We recently visited the Russian Wilderness for a trail working trip and I became re-familiarized with these two wonderful tree species.

Continue reading “Engelmann Spruce and Subalpine Fir in California”Five-Needle Pines Community Science Project

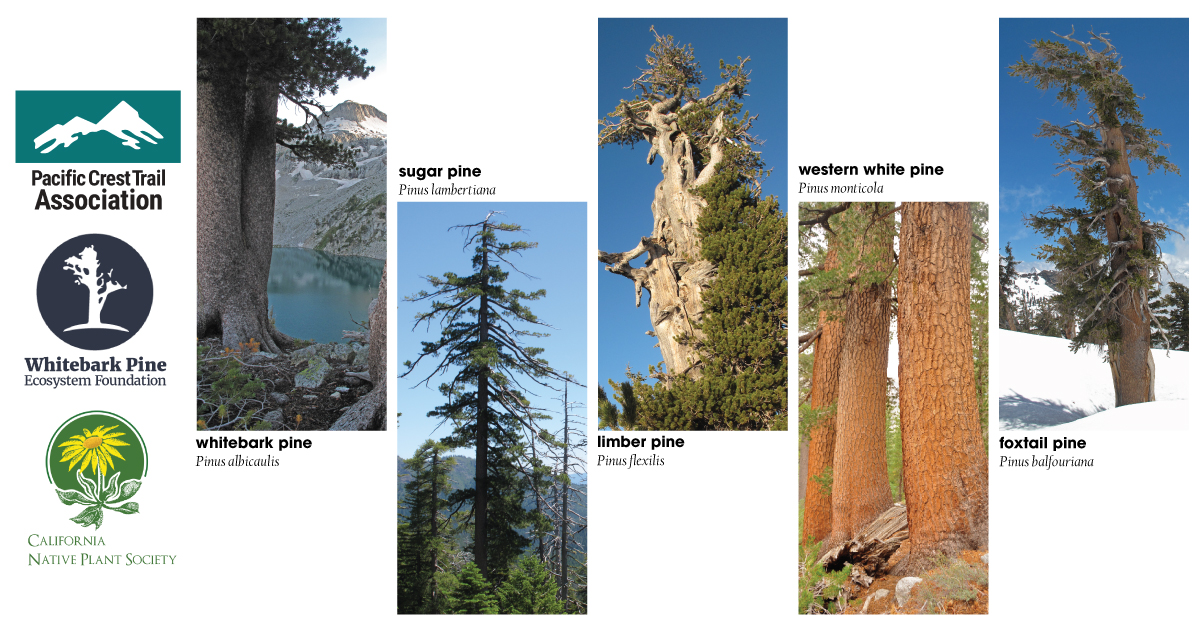

As a board member of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation, I decided to help cook up this project because all is not well with the five-needle pines of western North America.

Five-needle pines along the Pacific Crest Trail include the sugar pine, limber pine, foxtail pine, whitebark pine, and western white pine. Crucial to the mountain ecosystems where they occur, these trees face an uncertain future, and scientists are trying to learn more.

You can help and are invited

Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation has partnered with the California Native Plant Society and the Pacific Crest Trail Association to raise awareness about the plight of five-needle pines and conduct this community science project. The goal is to get thru-, section-hikers, and everyone who visits to the trail to map and inventory five-needle pines along the Pacific Crest Trail.

By participating, you will help increase awareness of the changes affecting our world while improving connections to nature. Working together to document what’s happening is a positive step toward recovery.

Continue reading “Five-Needle Pines Community Science Project”Trees in the Desert

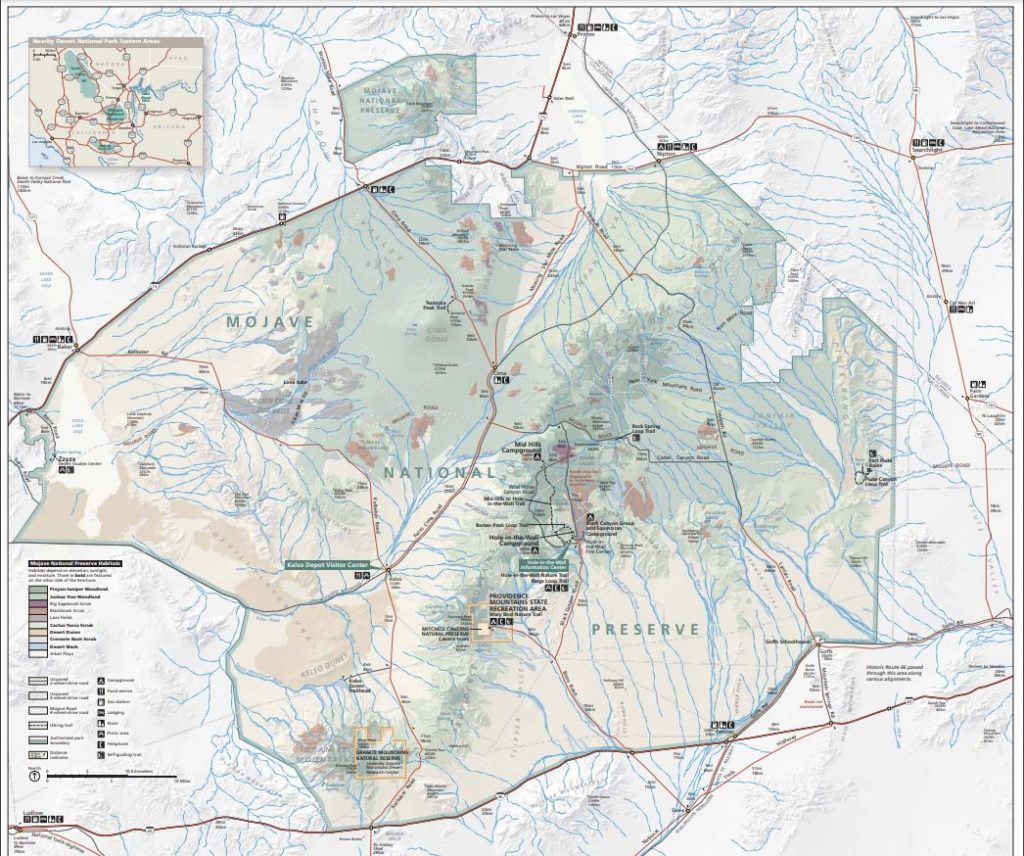

Exploring the Mojave National Preserve

Established in 1994, the Mojave National Preserve encompasses 1.6 million acres roughly bounded by Interstates 15 and 40. Most simply pass by this region on their way to other places (Lost Wages, Nevada for example) but it is a premier desert park. This vast and varied landscape includes dunes, dry lakebeds, granites, volcanics (domes, lava flows, and cinder cones), limestones, and sedimentary deposits which support a diverse collection of plants. The preserve includes creosote bush lowlands at 880 feet near Baker all the way up to conifer woodlands at 7,929 feet on the summit of Clark Mountain. The Mojave Wilderness is 700,000 acres of the preserve.

Within the preserve is the University of California Riverside’s Sweeney Granite Mountains Desert Research Center. The University of California’s GMDRC is dedicated to academic research and teaching and access is solely through an application approval process. This was was our basecamp. I am working on a book with Philip Rundel and Bob Patterson called California Desert Plants (Backcountry Press, late 2022) so we came to experience, explore, photograph, and write about the regional wonders. In particular, we wanted to find trees in the desert.

Magnificent Five-Needle Pines

of Western North America

I have made more posts about foxtail pines than any other trees and it is thus no secret that my favorite conifer is a five-needle pine. There are a lot of thoughts and details about five-needle pines swirling around in my world these days–for better or worse (fires and climate change)–so I figure I’ll add to the story with some updates here.

Continue reading “Magnificent Five-Needle Pines”Relearning the Southern Siskiyous

I am slowly learning about some of the shortfalls my training as a western scientist has had on my ability to interpret vegetation communities of the Klamath Mountains. What I am learning, that was never properly taught in my schooling, is that everything we see today in the Klamath Mountains was affected, to some degree, by long-term human habitation over the past ~9,000 years. For example, up north in British Columbia’s coastal temperate rainforest Fisher et al. (2019) found that the plant communities around village sites had different plant assemblages than control sites and were dominated by plants with higher nutrient requirements and a cultural significance. Consider this next time you look at an oak woodland on a river bench

Another major misconception taught in western science is the description of the assumed wild and wilderness as absent of human impact–when this is far from the truth. Much of what we have designated as wilderness was sculpted by Native People’s stewardship. For example, numerous travel routes were maintained for securing basketry, medicine, food resources, or reaching ceremonial sites (see map below).

Continue reading “Relearning the Southern Siskiyous”