A note for you, lover of conifers

A few years after the first edition was first published, I was deep in the Siskiyou Wilderness in search of yellow-cedar stands. To my surprise another backpacker came stumbling through the brush. After we said hello, he got a smile on his face as he pulled a copy of Conifer Country from his backpack and asked for an autograph. My heart swelled with joy as we discussed how to tell the difference between yellow-cedar and Port Orford-cedar with both the book and plants in hand. This experience was grounding and simply lovely.

It has been 12 years since Backcountry Press first published this book. My wife Allison and I launched the business to support that publication. We took this risk to tell the story of science in interesting and engaging ways–to inspire deeper connections to the Earth. Looking back, I am amazed at what this project has brought us and the connections it has helped establish with the land and its enlightened people.

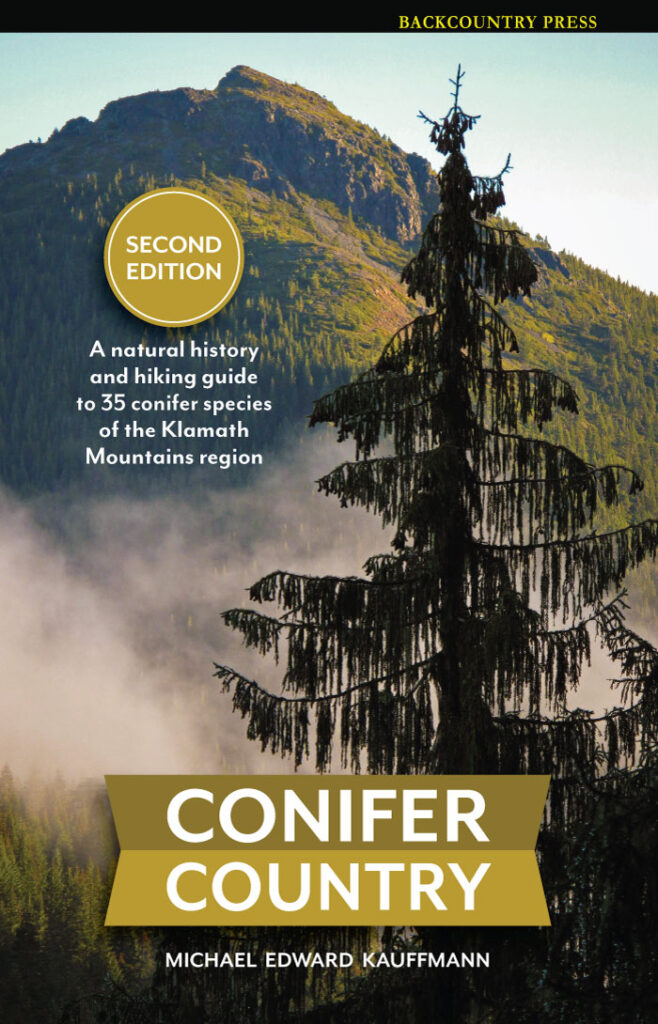

2012 found me graduating with a Masters from Cal Poly Humboldt for this book, welcoming our first child into the world, sending the first copies of Conifer Country into circulation, and buying our first home (in a redwood forest of course). Since that fateful time, this book and its sales have provided the engagement and means to grow Backcountry Press into a legitimate business with 14 books now in print. Over 12,000 copies of this book have been torn and tattered across the Klamath Mountain landscape. I’ve found work mapping these rare conifers to set baseline distribution and health data. I’m called a conifer ecologist now 😉

Creating Conifer Country (second edition)

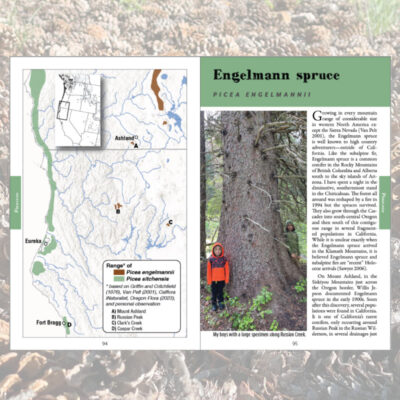

Change is omnipresent and this book needed updating over that time. Internet based community science platforms like iNaturalist have revolutionized and refined biogeographic data for all living things, including the conifers of the Klamath Mountains. Range maps have been updated. Introduced pests and pathogens are also driving swift forest changes. The balsam woolly adelgid has arrived in the Klamath since the first printing. Diligent scientists and land managers are watching the region’s rare firs to monitor for change. Average temperatures are on the rise, assisting in conifer decline when a tree’s energy balance is tipped by a hemiparasitic mistletoe or fir engraver beetle infestation—these are native species to which these conifers have coevolved within a more balanced climate regime. I have added discussions to relevant conifer treatments in order to tell these newly-developing story lines.

The regional climate is warming and drought which, when coupled with over 100 years of mismanaged forests, drives high intensity, large scale wildfire events. The Slater and Devil fires, started on a dry, windy late-summer afternoon in 2020 and ultimately burned 166,127 acres, claimed two lives, and injured 12 people. It moved so hot and fast that entire rare and ancient vegetation communities evaporated including all the Brewer spruce in the Matthews Creek Botanical Area. These trees were part of a weekend adventure I shared in the first edition. A visit now would find Oregon’s largest Brewer spruce and a top 10 Oregon Douglas-fir gone forever. I no longer include that destination in this edition.

In other ways, change has been slow across this vast landscape. The redwoods of northern California are still thousands of years old, ancient foxtail pines are slowly growing across the high elevation sky islands, and fire has reinvigorated stands of Baker cypresses. These are the experiences to celebrate and love.

There is so much to love for these places and the trees that call them home. I encourage you to take this book for a new adventure and find this love of place through trees. Climb a peak and sit by a Jeffrey pine like my friend John is doing in the picture below, walk along a river canyon and sit in the shade of a ghost pine, and then go home and share your love story for these conifers. With love comes stewardship–the trees need us as we need them. Happy conifer watching and, if I see you in the forest, please say hello!