With good reason, life brought us back to the southern Appalachian Mountains. My origins are in and around this region. The connection is bolstered by my deep love of the Klamath Mountains and the connections these two places share. We took a family hike–a new joy because our 5-year-old can hike with us now–to a special landscape near Asheville, North Carolina. Here we explored several rock outcrops of the southern Appalachians.

Continue reading “Rock Outcrops of the Southern Appalachians”Conifer Country (second edition)

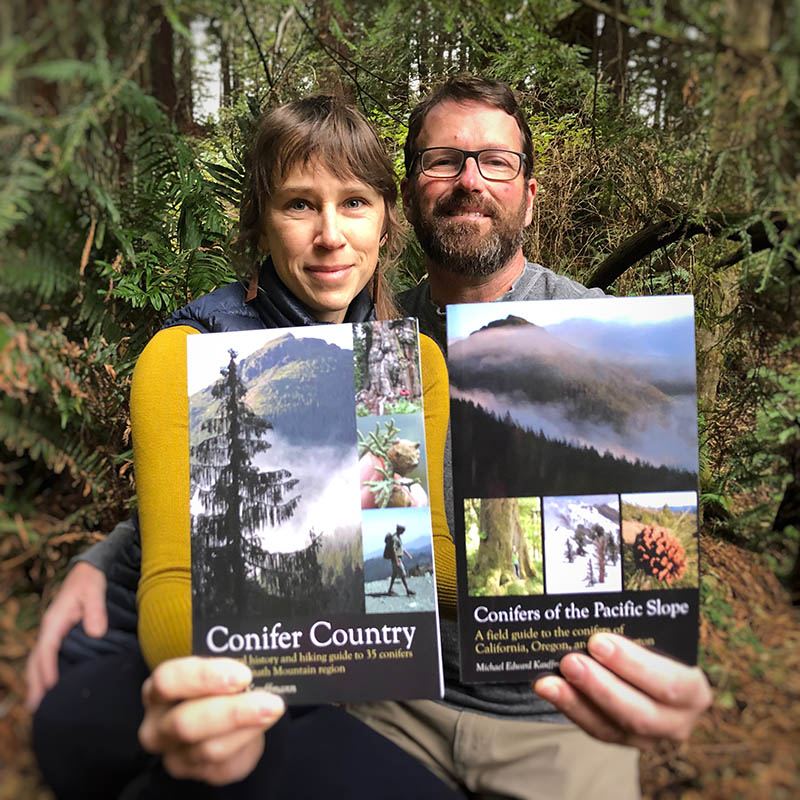

A note for you, lover of conifers

A few years after the first edition was first published, I was deep in the Siskiyou Wilderness in search of yellow-cedar stands. To my surprise another backpacker came stumbling through the brush. After we said hello, he got a smile on his face as he pulled a copy of Conifer Country from his backpack and asked for an autograph. My heart swelled with joy as we discussed how to tell the difference between yellow-cedar and Port Orford-cedar with both the book and plants in hand. This experience was grounding and simply lovely.

It has been 12 years since Backcountry Press first published this book. My wife Allison and I launched the business to support that publication. We took this risk to tell the story of science in interesting and engaging ways–to inspire deeper connections to the Earth. Looking back, I am amazed at what this project has brought us and the connections it has helped establish with the land and its enlightened people.

Approaching 50 in the Desert

In my twenties, I basically lived in the desert — just outside of the Mojave at 6,000′ in the San Gabriel Mountains. I was minutes from Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) that define a particular charm in the Mojave Desert . I spent many winter weekends wandering the Sonoran and Mojave deserts of California and Arizona. It was dreamy.

After moving north to the temperate rainforest of Humboldt County to pursue a more stable career and more conifers, the desert has become a less common destination. I have been back a few times but, honestly, not enough.

With 50 on the horizon, a few of my friends decided to meet up in Las Vegas and get into the desert as fast as possible. We spent time in the Mojave-Sonoran transition zone south of I-40 and could not have been happier–walking washes and scrambling through canyons. We saw new plants, plenty of rain, and reflected on our first half century around numerous campfires.

Continue reading “Approaching 50 in the Desert”Golden State Naturalist

I joined Michelle Fullner on her podcast the Golden State Naturalist. She states that it is a podcast “for anyone who’s ever looked around and realized just how much there is left to learn.” I was happy to chat with her.

We discussed my growth as a naturalist and how that brought me to write a book about the Klamath Mountains. We discuss ancient rocks, carnivorous plants, temperate rainforest, why people are a vital part of the story of place, and why the Klamath Mountains are bursting with a truly stunning array of beings and relationships. I hope you enjoy it–Michelle does a great job with her podcast!

Papoose Lake Revisited

Trinity Alps Wilderness

In November 2008, I made my first trip to Papoose Lake in the Trinity Alps Wilderness. That trip inspired my first blog post which evolved into Field Notes From Plant Explorations. This first post was more about geology than plants because of the unique geologic character of the Papoose Lake Basin.

This month, almost 15 years later, I returned to Papoose Lake to conduct vegetation surveys as part of our Klamath Mountains Vegetation Mapping Project. In many ways the basin is the same but in others changes are afoot. What follows are some reflections on 15 years of blogging through the eyes of a Klamath Mountain lake basin.

Continue reading “Papoose Lake Revisited”