An Old Friend in a New Light

I first met Blue Oak (Quercus douglasii) when I moved to California as a young educator, living and teaching at SCICON, a school nestled in the Sierra Nevada foothills above the Great Central Valley. The property was draped in a mosaic of oak woodland, and it was the blue oak—with its pale, ghostly bark and seasonally bare branches—that became a familiar companion during daily lessons with sixth graders. At the time, I didn’t fully grasp what I had stumbled into, but I knew it felt like home. As a kid raised in the deciduous forests of the Appalachians, these leaf-losing oaks whispered a comforting language.

That first year was a short chapter—one orbit around the sun—and then I moved. First to the pine and fir draped San Gabriel Mountains and then into the fog-wrapped redwoods and the towering conifer forests of the Klamath Mountains. I traded oaks for firs, pines, and hemlocks, immersing myself in the evergreen abundance of one of the most botanically diverse mountain ranges in North America. Blue oak slipped to the edge of memory, an old friend whose name I remembered but whose face I rarely saw.

Then, last week, our paths crossed again—unexpectedly and beautifully

While conducting plant surveys at the northernmost extent of blue oak’s range, I found myself at the southern edge of the Klamath Mountains. And there, perched on sunlit ridges, were the outliers—small, scattered stands of blue oak, tucked like relics into the folds of chaparral and the fringes of ponderosa pine forest. These trees live quietly and sparsely, tucked away where cows don’t bother to graze and ranchers don’t press their use. These are pockets of refuge, where acorns may fall and seedlings might actually grow tall enough to join the canopy.

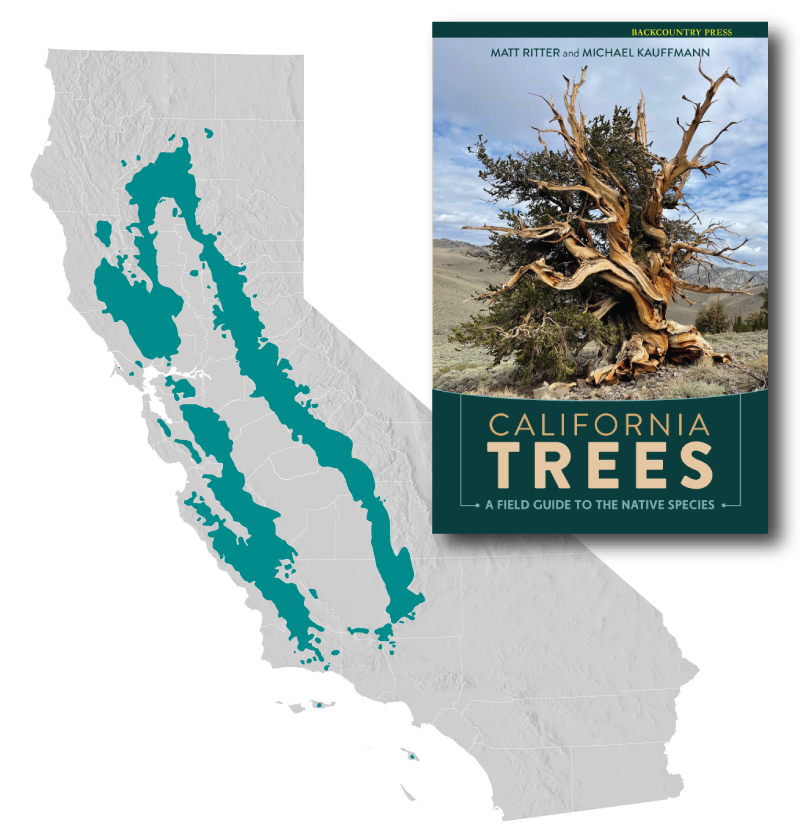

Unlike the central and southern parts of California where blue oak woodlands dominate millions of acres, these remnant groves are islands in time. In much of their range, especially in the Central Valley and Coast Ranges, blue oak ecosystems have been relentlessly grazed. The consequences are stark—seedlings are stomped, regeneration stalls, and the ancient giants of the woodland stand surrounded by empty ground where the next generation should be rising.

And yet, despite this, blue oak persists

It is a tree of endurance and elegance, found nowhere else in the world but California. It thrives in dry, rocky soils and can live for centuries. Its silver-blue leaves shimmer like distant water in the summer heat. It is both a keystone and a caretaker, supporting hundreds of species—from lichen to lizards, woodpeckers to wildflowers.

The biodiversity of blue oak woodlands is astonishing. These ecosystems harbor an incredible array of plants and animals, many of them uniquely adapted to the rhythm of oak leaf fall, acorn drop, and spring greening. Under the canopy of blue oak, native grasses and wildflowers still push up in early spring if they’re given half a chance. Acorn woodpeckers, with their clownish faces and staccato voices, chatter among the limbs. Insects find haven in the bark’s crevices, and shade-loving mosses thrive on north-facing trunks.

What struck me most in this recent encounter, standing beside trees I hadn’t spent much time with in decades, was the grace of survival. These blue oaks had found refuge beyond the appetite of hooves. Here, in these hidden northern coves, they were allowed to exist on their own terms—to leaf out, to drop acorns, to grow old in peace.

This gives me hope

If these small northern enclaves can persist, perhaps they can become models of resilient restoration. Perhaps we can learn to value what remains, to protect these stands not for what they once were, but for what they still are—and what they might become again.

To walk beneath blue oaks is to walk beneath history—both ecological and personal. For me, it is to revisit the young teacher I was, and to reconnect with the ancient lineages that have shaped this state’s landscapes far longer than we have walked among them.

May we listen to the stories they still tell.

Beautiful. I feel the exact same way of my early life in the foothills of the Santa Cruz mountains (Bay side). Oak woodlands are California to me. Live Oak and Blue Oak . The silkworms would fall on the really hot days.

Thanks for taking the time to share your connection to blue oaks Chad. I’m glad this piece resonated.

Is it okay to love a tree? Should we not love all trees equally? I think it’s okay. I suppose that it’s very particular, very personal experiences that build a connection to a particular species; but, being a spiritual person, I wonder if there can be deeper, more direct affinities. Blue oaks have “spoken” to me, close to my East Bay home in places like Mt. Diablo State Park and Sunol Regional Wilderness as well as on a friend’s property in the Sierra foothills just downhill from Grass Valley. The bluish cast, the narrowly grooved bark, some je ne sais quois in its branching – all good. Alas, I have other loves. The vast pure stands of Jeffrey pine southeast of Mono Lake are close to my heart, as are mountain hemlocks on the slopes of Mt. Shasta. Closest to home, in my own Dimond Canyon in Oakland, I hold great affection for the California buckeyes; and I set a personal, seasonal clock by their changes.

Andrew – Absolutely, it’s okay to love a tree—deeply and particularly. Love grows from familiarity, from place-based experiences that shape who we are and how we see the world. That personal connection to a species doesn’t mean we love others less—it simply reflects how landscape and memory entwine.

As we experience the stress on our more northern species, it would be interesting to see if Blue Oak could survive the jump to Shasta, Scott, or Bear Creek/Rogue Valleys. Ungrazed lower slopes exist, and a trial would only require a pocketful of acorns…

The Canadians are trying this strategy with some of their southern species, establishing controlled trials in appropriate more northern sites. Whitebark Pine is an example that the BC Forest Service is attempting. Our US Forest Service research was once the envy of the world, but has been gutted and its scientists are mostly gone or are not supported with adequate budgets. Passionate people make great citizen scientists! Thanks Michael for all the great work you do in support of our ecosystem awareness.

Dean, I agree—there’s both ecological value and poetic resonance in the idea of Blue Oak finding a future foothold in the Shasta, Scott, or Rogue River Valleys. These areas, especially the ungrazed lower slopes you mention, could offer critical microrefugia as our climate continues to shift. I’ve been following the assisted migration trials in Canada as well, and the example of Whitebark Pine is particularly moving—especially given its ecological importance and vulnerability.

You’re also spot on about the erosion of U.S. Forest Service research capacity. The loss of institutional support is troubling, but I take hope in the passion of citizen scientists and community-led projects that are stepping in to fill that void. Thanks for your encouragement and for keeping these important conversations alive.

Hi Michael, I was surprised to see SCICON receive a shout out! I am from Kings County, went to HSU and lived there on/off for 10+ years, then moved back to the Southern Sierra/Tulare Lake Basin. I am a working lands wildlife ecologist with Point Blue and am currently working with SCICON’s Circle J Ranch on a blue oak enhancement project. This spring across the Southern Sierra region, I have observed an amazing number of blue oak seedlings within cattle grazed ranches, triggering thoughts of potential response to good water years after severe drought. Beyond seedling protection with browse exclusion cages, I am documenting if any of the unprotected seedlings make it. As part of work, we are also experimenting with planting acorns from blue oaks in Tulare County up in Sonoma and Shasta to test for drought tolerance and climate adaptive capacity of seedlings compared to local genotypes.

I strongly relate to the ecological and spiritual magic of blue oaks and appreciate your musing on them this week. Cheers!

Brian- Thank you for your kind words—and what a cool connection! When I worked at SCICON, they had just acquired Circle J Ranch, and I remember the excitement around its potential for education and conservation. It’s incredible to hear that you’re now involved with blue oak restoration on that very land. Your observations about seedling response after recent wet years are fascinating, and I’m especially intrigued by your climate adaptation trials across counties—important and hopeful work. Grateful to be in community with folks like you who share reverence for the blue oak and its resilience. Cheers!

In the spirit of the Bigfoot Trail (which is oddly enough what connected me to you years ago as I once managed HSVTC, a trail crew in the Sierra based out of Fresno), I have been dreaming up a trail in the Southern Sierra that connects the spectacular diversity of ecosystems. A path that celebrates the massive (in DBH and height terms), gorgeous deciduous trees and conifers down here, following rivers from Central Valley floor to alpine Sierran highs. The conundrum is navigating private property. I have the honor to work on beautiful ranches and see immense biodiversity, yet opening them up to public recreation is highly difficult (I refuse to say impossible). The largest dbh blue oak I have seen thus far in my life is technically on a publicly accessible ranch in Tulare County but many of the treat trees are inaccessible to most folks. Thanks for the opportunity and inspiration to share this seed of an idea. One of these days I will help BFTA bring dreams to reality, happy trails!

During the Carr fire near Redding a small stand of blue oaks were burned/ involved in the fire tornado. Namely right in the eye of said tornado. Those trees immediately in the eye were mechanically damaged by the wind but the trees within 50-100′ were killed by the fire.

To me it is surprising that the blue oaks have survived in our fire visited ecosystems. Now when I see blue oaks my curiosity leads me to take a longer look at the ecosystem involved.

Charley- Thanks for sharing that observation—what a dramatic scene those trees must’ve endured. I’ve been watching blue oak recovery along my drives on Highway 299, and it’s remarkable how they continue to persist, even in landscapes deeply reshaped by fire.

I enjoyed this piece. It made me think of the blue oak woodland I used to explore south of San Jose. I now live just south of Q. douglasii’s southern mainland extent – or so I thought. In exploring Simi Valley, Moorpark, and Thousand Oaks, here’s a scattered handful of Q. douglasii hybrids with the local scrub oaks. Mostly diminutive, but there are a few actual trees too. It’s remarkable. Seeing the blue-green foliage amongst the sheen of coast live oak will never get old.