I learned about this project in 2014 and have been following it closely ever since. In late April, 2020 my friends Justin Garwood, Ken Lindke, and Mike Van Hattem (with other co-authors) published the first definitive paper on glaciers in the Klamath Mountains. While the news is bleak, their diligent research documents the changes in the Klamath for hundreds of years through the eyes of the highest peaks and watersheds in the range. Please enjoy the summary that follows.

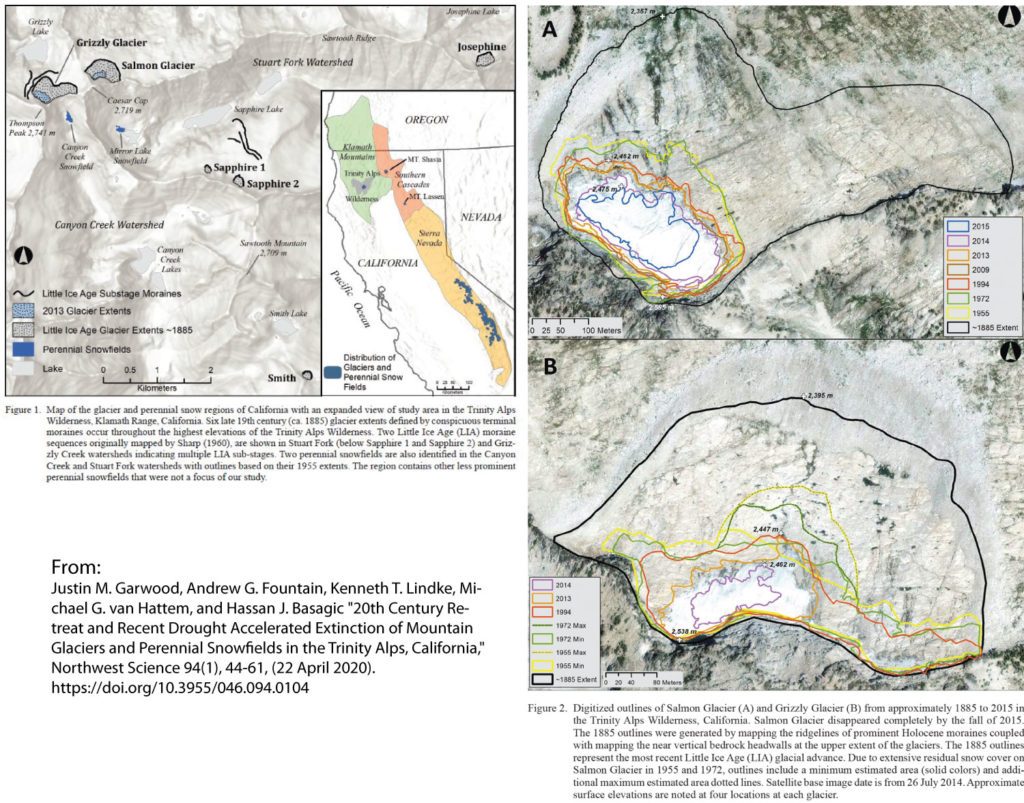

Justin M. Garwood, Andrew G. Fountain, Kenneth T. Lindke, Michael G. van Hattem, and Hassan J. Basagic “20th Century Retreat and Recent Drought Accelerated Extinction of Mountain Glaciers and Perennial Snowfields in the Trinity Alps, California,” Northwest Science 94(1), 44-61, (22 April 2020). https://doi.org/10.3955/046.094.0104

Excerpt from The Klamath Mountains: A Natural History (2021 release)

The two highest elevation perennial surface waters in the Klamath Range begin as glacier and snow meltwater above 8,000 ft (2,450 m) cascading down north facing slopes of the Trinity Alps crest. While these streams originate within one kilometer of each other, their respective watersheds are separated by 177 stream miles (285 km). The Salmon Glacier stream drains to the South Fork of the Salmon River while the Grizzly Glacier stream feeds the North Fork of the Trinity River. Both eventually meet where the Trinity River enters Klamath River at Weitchpec.

Until recently, Grizzly and Salmon glaciers of the Trinity Alps have represented the lowest and western-most glacier ice in California, persisting 1,700 feet (518 m) below all other California glaciers—only found on Mount Shasta and across the southern Sierra Nevada (see figures below). Here, in the coldest and most rugged niche of the Klamath Mountains, snow accumulation far exceeds that in the surrounding landscape. Unique topographic properties of Thompson and Caesar Cap peaks produce exceptional snowpack necessary to maintain glaciers at these low elevations. Conducive features include northeast aspects, tall headwalls, snow avalanching, and windblown snow recruitment from the summits. Furthermore, the proximity of these high cluster of peaks to the Pacific Ocean produces unrivaled regional precipitation levels.

The massive glaciers of the Pleistocene Epoch (spanning approximately ten thousand to two million years before present) shaped the rugged pyramid summits, excavated hundreds of bedrock-lined cirque lakes, and carved dozens of long shadowed U-shaped canyons found across the Klamath Range today. During the Little Ice Age (LIA), a 700-year period lasting from around 1300 to the 1880s, glaciers were much smaller, clinging to the north slopes of the highest summits of the Trinity Alps. At least five LIA glacier locations and three LIA glacial substages have been identified in the Trinity Alps based on remaining rocky terminal moraines. Grizzly and Salmon glaciers represent the largest of the LIA glaciers and the only two persisting into the 21st century. Unfortunately, beginning during the catastrophic five-year California drought of 2012-2016, Salmon Glacier melted away and Grizzly Glacier partially broke apart (stagnated) by fall 2015 but still persists in 2020.

While the demise of these small Klamath glaciers is seemingly insignificant from a global perspective, they offer a unique local climate signature by measuring Earth’s responses to changes in temperature and precipitation. These changes will resonate in the diversity of the regional flora and fauna that depend on cold relictual habitats. Species in these habitats are still being discovered, like ice-loving beetles and ice crawler insects found to be endemic to Grizzly Glacier. Coldwater stream niches fed by glacier and perennial snow meltwater also support genetically distinct stenothermic stream fauna including the world’s highest populations of Coastal Tailed Frogs and relict populations of spring Chinook Salmon and Summer Steelhead.

The first comprehensive regional natural history is here!

Edited by Michael Kauffmann and Justin Garwood.

I have admired the Trinity Alps and Siskiyou Mountains, since the 1950s. My father and uncle owned and restored the old Lewiston Hotel, near the old Lewiston Bridge in the early 50s. I worked for the forest service in the late 70s, on the Pacific Crest Trail, and fought the wildfires at Forks of Salmon in the fall of ’77.

Sad to hear of the loss and decline of these vital features, on the land that means so much to the memories I hold so dear.

I spent five years in the late 70’s and early 80’s a wilderness ranger in what is now the Trinity Alps Wilderness. Had the privilege of gazing upon each of the glaciers mentioned — both from afar and close up. I look very forward the buying a copy of this book.

Thanks Jay- the book is about a year away but will be amazing. The group of authors is top notch and their stories are important.

Very enjoyable to read and view photos. This is the most contemporay “reports” I’ve seen on the Klamath Mtn. glaciers. Summer of 74 I was Wilderness Guard in the Marbles. I recall a particularly long lasting snow bank tucked in on the north slope above and down to shore Rainy Lake which is below 5,400…well shaded and forested, no doubt augmented by avalanche. It was still pretty robust when I last viewed in mid Sept of 74. Got me to thinking of places where the “lowest” snow banks persist in the Klamaths.

Bill- Thanks for the comment. I am intrigued by your reflection on the snow bank below Rainy lake and you pose a good question! I wonder if the lowest elevation snowbank is below Devil’s Peak in the Siskiyous.

I think it was 86, ava

lanch snow lasted the summer, east side of Canyon Creek Meadows, 4500 ft

Very welcome insight. Appreciating this research. Concerned about climate change. Loving the Klamaths! THANK YOU

You and Justin have to meet!

I do most of my backpacking in the Yosemite area, from the Emigrant Wilderness down to Ansel Adams and John Muir wilderness areas. There is evidence of glacial action everywhere, from polished rock domes, to stray boulders on polished granite sheets, to scooped-out lakes surrounded by rocks. What happened to those glaciers?

Joe- As the paper better explains, the Klamath Mountains are drying and warming. The fact that these glaciers have persisted since the end of the Pleistocene, at such low average elevations for their latitude, is amazing in itself.

Cirque basins are all over the place in N. Calif and S. Oregon. “U” shaped valley profiles (as opposed to “V” shaped) begining with a horshoe shaped cliff headwall with a lake at the headwall’s base. The two most absolutely classic cirque basins in the area are Trail Gulch and Long Gulch Lakes in Siskiyou County.

I first became aware of the Thompson Peak Glacier in the early 1970’s when I worked for California Fish and Game as a seasonal. It looked at that time like it was on it’s last leg. I would hever have believed that it would still be hanging on 50 years later.

By the mid 80’s when our eldest was old enough to go, we were often backpacking to our favorite lake in the Trinities, Grizzly. At that time the glacier above Grizz was substantial and our trips always included some exploration on and around that ice. It was quite thick with an impressively deep bergschrund. I even bought a light climbing rope to have on those trips for rescue, just in case, as I remember a few crevasses deep enough to be a hazard. So sad that in recent years the remnants of it could not easily be called a glacier, though technically may have been, as one of them likely survived the summer and autumn heat to became a base for the next winter’s snow accumulation. Every time I’ve been to Grizzly Lake it’s impossible not to imagine how that basin may have looked when filled with the glacier that formed it, with no doubt impressive ice-fall due to the big drop at the rim of the lake basin, even though the ice surface would have been far above the granite. I remember seeing what looks like a small terminal moraine in the drainage north of Caesar Cap Peak, likely from the more recent Little Ice Age. So very sad to see these recent changes.