Original Publication DATE: 10/12/2009 2:23:00 AM

I had often pondered a high and extensive ridgeline in the middle of the Trinity Alps Wilderness from other mountain top vantage points on which I stood–at one point or another–in my adventures in the Klamath Mountains. It took me several years to realize this jagged range had its own name and many years more to actually get to this isolated place. Finally, in October, I climbed my way into the high country known as Limestone Ridge. I had read this extensive ridgeline (over 3 miles long) was one of the best examples of Karst topography in western North America. This summer, the spectacular Marble Mountain was my first introduction to Karst limestone landscape in the Klamath so I assiduously pursued a chance to see more. With those distant images and arresting words burned on my brain I was finally climbing–up–up–up–from Hobo Gulch in the Trinity River Canyon.

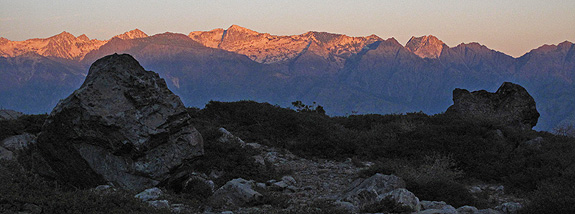

Ascending a spectacular creek canyon, I couldn’t help but notice that fire had recently passed through most of the forest. It was a good burn. The understory of saplings had been consumed, but the fire’s crown only climbed 30 or 40 feet so the majority of large trees had only scars on their trunks. This was surely prophecy to the ‘natural management plan’ set into action by lightning last summer and fall. As I climbed higher–eventually out of the canyon and onto rigdelines–the fire’s scars became more prodigious. As the picture above indicates, when the montane chaparral caught fire, everything around burned. Since the elevation of Limestone Ridge peaks at 7,500 feet, the montane chaparral–with proper slope and aspect–can grow to the tops of the mountains here. Because of that, the fire ravaged a large percentage of the trees in the high country. What was left appeared to be small unburned groves in isolated pockets generally tucked in north-facing cirque–where the chaparral did not reach.

Once we had climbed into these glacial cirques and away from south-facing hillsides, we discovered that these nooks had offered a refuge for sublime subalpine forests. Thick stands of mountain hemlock, Shasta fir, western white pine, and Pacific yew continued to thrive–sheltered from the fires–in and amongst an atypical array of colorful rocks.

Dennis Cox and Walden Pratt did reconnaissance studies here in the early 1970’s–a region which they deemed “remote with access extremely difficult.” There goal was to attempt to reconstruct and understand the tectonic events which occurred during the middle Paleozoic and early Mesozoic. They discovered unique areas of “submarine chert-argillite (associated with limestone) slide-breccia” which had never been reported from the Klamath Mountains. Just to the east of this discovery–along the spine known as Limestone Ridge–is a melange of jumbled rock consisting of “massive metabasalts intruded by gabbro and serpentinite.”

Abel Jasso, the Forest Geologist with Shasta-Trinity National Forest describes the area to me in an email by saying:

“A band of diabase, gabbro and serpentine underlies Limestone Ridge. It is bounded by the North Fork fault on the east and by the Twin Sisters fault on the west, Both faults contain abundant dikes of sheared serpentine. The diabase is a medium-grained rock composed of augite and oligoclase (a mineral of plagioclase feldspar). It has undergone low-grade metamorphism. The gabbro is a coarse-grained diallage-labradorite rock (clinopyroxene). During the last period of orogenic activity stocks of tonalite and diorite intruded the diabase and serpentine of Limestone Ridge. Limestone Ridge? Go figure.”

So although certian minerals that are present in limestone are present on Limestone Ridge, limestone is not to be found here. But, if you are motivated to follow steep, seldom used trails into exquisite country; geological blunders coupled with botanical wonders await you–the temporal visitor–on this adventure into the Trinity Alps Wilderness.

References:

DENNIS P. COX and WALDEN P. PRATT, Geological Society of America Bulletin 1973 v. 84, p. 1423-1438.

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Slate

DATE: 8/8/2012 2:08:51 AM

“geological blunders coupled with botanical wonders await you”. I am awestruck. Planning next year’s adventure now! Thanks for the review plus fabulous pics.

I have read most every blog you have posted concerning the klamath mountains. I was fortunate in having lived most of my life in the siskiyou mountain area. I noticed when very young ( grade school ) that the plant communities I hiked through did not resemble those elsewhere outside the region. This has become a lifelong passion to observe and find locations where rare and/or relic species of plants occur. If you have any web sites or publications available concerning topics concerning conifers, the klamath mountains, rare plants,etc, I would greatly appreciate it.

Thank you!

Thanks Eric! We are working on a Natural History of the Klamath Mountains book — stay tuned! I also just published a new book on the Wildflowers of the Trinity Alps you might find of interest.