North America holds two of the most species-rich temperate forests in the world: those of the southern Appalachian and Klamath mountains. What do these locations have in common? Glaciers and seas did not completely cover them during the Cenozoic and the mountains were monadnocks, or islands above the plains, offering temperate refuges to plants and animals over time. Both locations have historically maintained a moderated climate. These areas are beyond the southern terminus of the enormous continental ice sheets of the Pleistocene. Some plants undoubtedly remained in these regions through historic climatic change, while other species repeatedly moved in as climate cooled and glaciers pushed southward and then moved out following glaciers northward. These dynamic fluctuations have cradled plant diversity in these two unique regions.

The current consequences of these historical patterns are that the Klamaths and southern Appalachians have grand floristic diversity, a concentration of endemic plants, and a fundamental importance to the forest floras of nearby regions (Whittaker 1960). Per unit area, the Klamath Mountains and the southern Appalachian Mountains hold more plant taxa than any others in North America. Plant genera such as Cornus (dogwoods), Asarum (wild ginger), and various conifers (Pinus, Abies, Thuja, Chamaecyparis) grow a continent apart while providing a comparative glimpse of an ancient flora.

-From Conifer Country

The Atlantic white-cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) and the Chester Cedar Swamp

My family and I made a Connecticut “migration” in July of 2014 to visit family near New York city. While I was looking forward to family time, I wondered if there could possibly be and natural, wild space anywhere near the largest population center in the country. A google search revealed that Connecticut does indeed have a few Natural Landmarks that preserve and celebrate the states geological and ecological heritage. I picked one to visit that was relatively close to our “home” as well as one that celebrates one of the most ancient lineages of plants on Earth – a conifer!

There are two species of Chamaecyparis in North America and four more sprinkled through Taiwan, Japan, and China. Lovers of the Klamath Mountains are familiar with Chamaecyparis lawsoniana, which is a Tertiary relict, finding refuge here after millions of years of climate change. In northwest California and southwest Oregon it prefers the cool and relatively wet Mediterranean climate. Climate changes since the beginning of the Tertiary have cause the species to contract its range toward the coast where it survives on a variety of soils but requires significant winter precipitation.

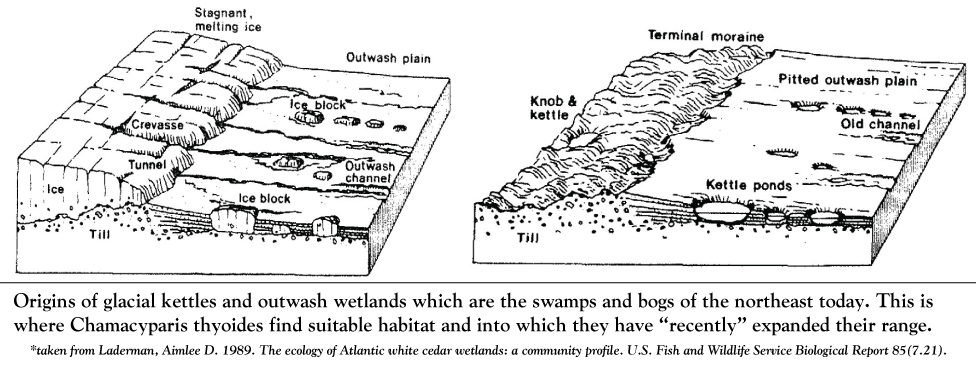

On the East Coast, Chamaecyparis thyoides has been “pushed around” since the Tertiary as well. In the Pleistocene large sheets of ice pushed southward thus restricting the Atlantic white-cedar to un-glaciated regions along the coast. With a warming climate and retreat of glaciers, the species is experiencing a northward migration into the the kettle ponds and outwash channels left behind by the retreating glaciers. These are the current swamps and bogs of the northeast.

Unique assemblages of plants live in the freshwater bogs and wetlands inhabited by Atlantic white-cedar. Acidic waters are a refuge for species that are rare or endangered regionally. Swamps nurture habitat for species at the geographic limits of their ranges while many locally common aquatic plants and animals are absent from cedar swamps (Laderman 1989).

The Chester Cedar Swamp was difficult to find and even more difficult to access. But I was able to penetrate the edge of the swamp and enjoy the unique assemblages of plants and animals found here. Based on pollen records, the Atlantic white-cedar have only been in this region for about 4,000 years (Laderman 1989). Which, to a conifer biogeographer, is an exciting phenomenon. An ancient plant that is pioneering “new” habitat is always exciting to see.

Resources:

- Laderman, Aimlee D. 1989. The ecology of Atlantic white cedar wetlands: a community profile. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Report 85(7.21). 114 pp. DOWNLOAD

- Whittaker, R. H. 1960. “Vegetation of the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon and California.” Ecological Monographs 30:279-338.

- Connecticut Natural Heritage Site: Cedar Swamps

- Cockaponset State Forest

- Chamaecyparis on the Gymnosperm Database