Original Publication DATE: 5/16/2011

Gary Lester is an explorer. With each day’s journey he refines an understanding of the natural world that has been cultivated from an early age. Because of his keen sense of place he has made a multitude of significant ecological discoveries. Any one of these discoveries, considered alone, would be a lifetime’s achievement for some (like me) but seen together Gary’s findings are regionally paramount and set the bar high for naturalists everywhere. For example, in the fall of 2010, he and his wife Lauren identified a Brown Shike in coastal McKinleyville that created quite a stir for birders nationally (he has show this bird to people from across the North America all winter, including a man from Florida who gave him the slick Tampa Bay Rays hat he is sporting in the picture below). Clearly, Gary has a view of the world where the smallest details build the bigger picture. When a new element does not fit that picture a personal discovery is made.

Saturday morning we joined Gary for his annual walk to Elk Head as part of the Redwood Region Audubon Society field trip series. Gary returns here often to make new observations and share previous intuitions fostered through long-term, place-based associations here. Trinidad State Beach has repeatedly offered a bonanza of rare events (each instance with a compelling story). He would share these experiences and more with us today as we birded and botanized.

In the parking lot before the walk began Gary explained some what we might expect to see. Wilson’s warblers and pelagic cormorants should be common, Swainson’s thrushes might be heard, and the anticipation of the ocean views hit a crescendo when he relayed that a pod of four Orcas were spotted off shore just yesterday. Gary reminded the group that none of the birds and mammals were guaranteed sightings, but if we watch carefully we would increase our chances. He also had a surprise up his sleeve–a rare species he guaranteed we would see; something that had endured climatic change here for thousands of years.

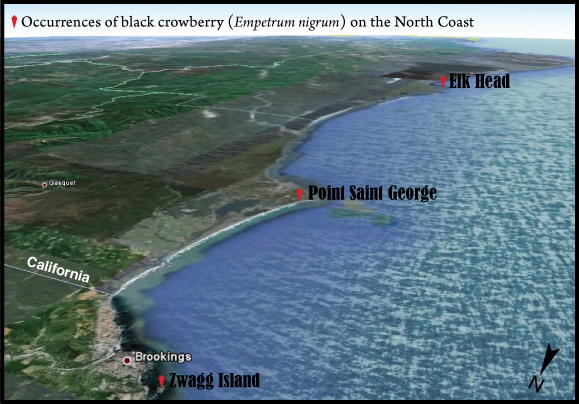

In the early 1970’s Gary was an undergraduate at Humboldt State University, building the foundations of his knowledge about the natural world. At that time (and even today) the ecological studies of the region were far from refined and his professors challenged him to assist with building the foundations of this knowledge base. In his research, Gary learned of two pioneering botanists1 in Del Norte County who had described thousands of regional plants–many of them for the first time. Ruby Van Deventer, and her husband Arthur, were rural scholars with a regional passion. Together they explored Del Norte County documenting their observations based on long-term associations with a landscape. As Ruby described, Arthur sketched and Gary Lester ultimately heard rumors of these discoveries. One such description was made for a plant common in the arctic tundra that the Van Deventer’s found in the coastal grassland scrub of Point Saint George near Crescent City. Upon reading about this, Gary made an appointment to talk to Ruby.

According to Ruby, the couple originally found black crowberry on Point Saint George by way of acrobatic botanical reconnaissance. Ruby spotted the plant down a steep cliff-face and, in order to access a sample, had her husband hold her ankles as she hung down the cliff to collect it. This was the first documentation in California for a species common in the subarctic–where it flourishes on open tundra and in spruce forests. Ruby hinted to Gary that the plant could be found in Humboldt County. Gary knew it had never been documented south of Point Saint George–he wanted more details and asked Ruby for them. Ruby’s staunch reply was “Young man, if you look hard enough you will find it!”

The challenge had been issued and Gary had no choice but to comply.

This is a powerful story in many ways. I think the most important lesson has to do with how one consciously and unconsciously goes about understanding the world. I believe it begins with repeated authentic experiences in nature—hands-on experiences that lead to holistic understandings. We need to experience wild emotions in an array of degrees—even misunderstandings we are challenged to conceptually change. Our world won’t evolve if we remain plump and entitled. Our species needs to be able to deal with, experience, and know places devoid of concrete. We need to get lost—finding time to play like Thoreau or Muir (or Ruby or Arthur or Gary).

When the intrepid explorer spends enough time looking, intuitions arise and a sense of place solidifies. These are the moments of discovery–whether it is a range extension, a migratory vagrant, or simple comfort found being somewhere alone. Experiences like these need to be a part of each or our lives. Discoveries can be made every day and, in fact, may become more common as we accelerate the Earth’s climatic metamorphosis. All we need to to is keep asking questions. Gary has watched the southern extent of the puffin breeding ground disappear over the last 9 years–why is this happening? These ecological outliers are harbingers for change and one purveyor of said discoveries. The crowberry, too, is an outlier…

Gary watches the other biota because he cares greatly. He, and many others, are role models for me as I refine my observation skills and begin to intimately understand the natural world, place by place. He models what it means to care for a place you love. I challenge you (as I do myself) to get out, go on field trips with local experts, learn something new, and be a keeper of the natural world. With practice and a bit of luck, we may each one day be led by birds to plants and back again–gaining an understanding, piece by piece, along the way.

1. A Rare Botanical Legacy by Ruby and Arthur Van Deventer. Edited by Rick Bennett and Susan Calla. 2009. Heyday Books. Berkeley, Ca.

Author’s Note: I would like to thank Gary for leading this walk and taking groups to his secret places. This is surely one of the most unselfish acts. The specimens of black crowberry at Elk Head are severely impacted by erosion due to the steep slope and also by foot traffic through the area. If you visit, please promote proper stewardship by staying on the trails and treading lightly.

COMMENT:

AUTHOR: Allison

DATE: 5/16/2011 6:31:07 PM

Thank you, Gary, for sharing your Empetrum story. And thank you, Michael, for sharing Gary’s story with those who were not lucky enough to hear it in person