As spring transitioned to summer, we traveled deep into the Coast Range to the headwaters of the Bigfoot Trail. Mount Linn—at 8,098 feet, the highest point in California’s Coast Range—rises like an island above a sea of rugged ridges and folded drainages. Here, the Bigfoot Trail begins, and here, we spent our days working to open the path for future hikers—treading, clearing logs, and feeling that familiar rhythm of shared labor in wild places.

Trail Work and a Journey to Mount Linn

With friends and family, we hauled tools, cut through wind‑thrown logs, and restored tread where winter storms had clawed the earth. The work was satisfying, connecting us to a lineage of stewards who keep these high trails alive.

But we also gave ourselves a gift: a day off to climb to the summit itself. We crunched over lingering snowfields, laughed as our kids slid and threw snowballs, and gazed out across the Coast Range, Klamath Mountains, and even the Great Central Valley all the way to the Cascades before turning our attention to a very special grove of trees.

The Southernmost Grove of Klamath Foxtail Pines

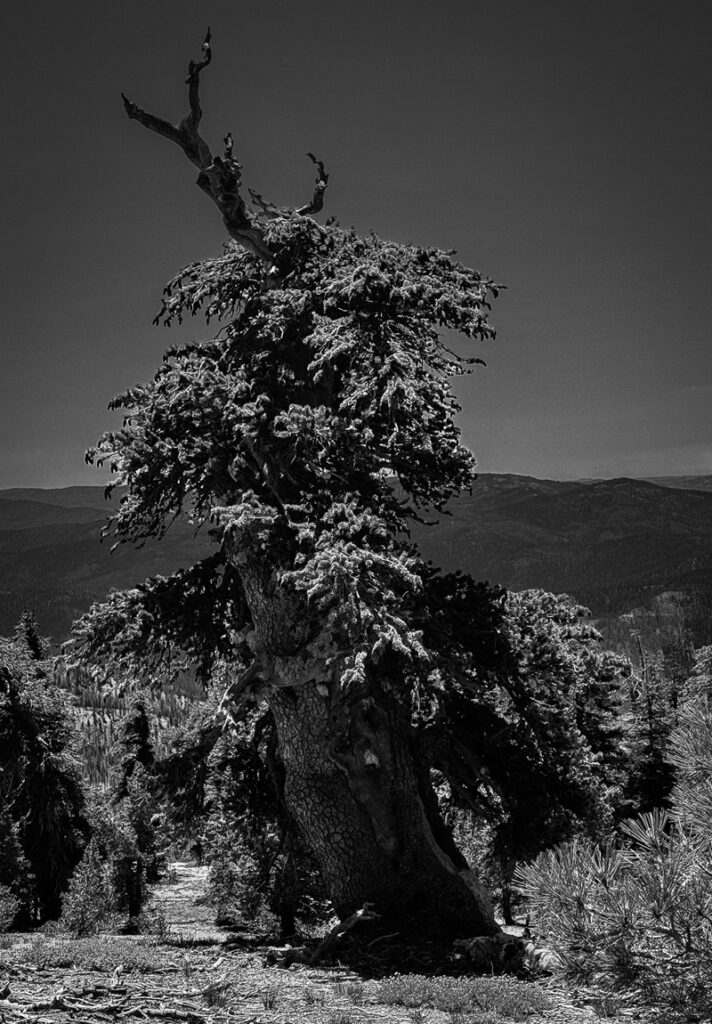

Near the summit of Mount Linn grows an extraordinary relict forest: a stand of Klamath foxtail pines (Pinus balfouriana ssp. balfouriana). Only about 15 acres in extent, the grove is hemmed in by sheer, glacially carved slopes to the north and vast rocky outcrops to the south. Here, twisted, amber-barked trees endure wind, ice, and sun—many of them easily over 500 years old.

I first documented this grove in 2009 and again in 2016, amazed by its isolation and resilience. Nearly a decade later, I returned with new questions.

Assessing Fire Impacts on Klamath Foxtail Pines

In 2020, the massive August Complex fire swept across much of the Coast Range. One purpose of my visit was to determine whether those flames had reached these ancient Klamath foxtail pines.

To my relief, the main stand remains remarkably healthy—almost exactly as I remembered it. The August Complex never entered the grove. There was only a small burned pocket, likely ignited by a lightning strike, which killed two old trees and singed a few saplings before self‑extinguishing, perhaps aided by a helicopter water drop.

Searching for Pests and Pathogens

This visit to Mount Linn marked the very first stop in a larger effort our vegetation mapping team is undertaking throughout the Klamath Mountains in 2025. All summer, we’ll be traveling to many known grove of foxtail and whitebark pines across this region, carefully assessing the impacts of white pine blister rust, bark beetles, and other emerging threats.

Mount Linn was our starting point, and what we found there was heartening: no signs of blister rust or beetle activity, vibrant needles and fecund cones, and trunks that remain strong and unscarred. This grove of Klamath foxtail pines is thriving—and it sets the stage for the many assessments still to come. Stay tuned as we share what we discover in the months ahead!

Hope for Klamath Foxtail Pines in the Anthropocene

To stand among these trees is to feel time differently. They have survived millennia of snowstorms, lightning, and drought. And yet, we live in an age of rapid change. The Anthropocene brings warming temperatures and drier summers that test even the hardiest species.

Still, here on Mount Linn, these ancient Klamath foxtail pines endure—quiet sentinels on the edge of California’s Coast Range, guardians of a past that still breathes in resin and wind. May they continue to thrive for centuries more.

Thanks for the write up Michael. I remember roaming out that way in the spring of 2015. I haven’t had a chance to revisit the Mendo in over 10 years and wonder how much is even reachable after many large fires.

Thank you for sharing that memory! Spring out there has such a special energy—wildflowers, creeks running clear from the last snowmelt. A lot has changed on the Mendocino since 2015, and yes, some areas have been reshaped or made harder to reach by the big fires. But trails are slowly reopening…

So great running into the Bigfoot Trail Alliance group out there! Thanks for the outstanding trail work. And for your series of Klamath Foxtail blogs through the years—it’s great getting a sense of the changes you’re documenting.

Just returned from an 8-day backpack among the southern Foxtail in the Cottonwood Lakes and Miter Basin area. The road that switchbacks up over 6,000’ from Lone Pine to the trailhead is worth a day’s study on its own! Cottonwood Lakes TH is full of foxtails that one can drive to—a special treat for folks who might not be able to get into the backcountry.

All the best! Long live California conifers!

Darla

Darla—thank you! It was a treat running into you out there, and I’m so glad the trail work and those foxtail posts have been meaningful. Your Cottonwood Lakes trip sounds incredible—those southern groves have such a different feel, yet the same ancient resilience (with scarily no reproduction of note). And yes, that road climb from Lone Pine is its own kind of pilgrimage through geology and elevation zones.

Here’s to many more miles among California’s conifers! Safe travels on your next adventure.

I’m not sure what counts as reproduction exactly, but we were wildly impressed by the numbers of seedlings and saplings we saw – the stands we explored looked very healthy and robust. Cone production was rockin’ as well. Happy to share some photos or more impressions if you’re interested!

I’ve hiked around the southern parts of the Yolly Bollys so many times and missed these amazing trees every time. I’m so glad the August fires spared this grove. I can’t wait to go back and look for them.

It’s amazing how these ancient trees can hide in plain sight, even for those of us who know the Yolla Bollys well. I’m equally grateful the August fires spared this grove—it feels like a small miracle. I hope your next visit leads you right to them!